What is a castle – some thoughts

One of the questions that occurs fairly regularly in castle studies is on the surface a simple question – but one in which there is no simple answer. That question is “What is a castle?” It is commonly answered with various well-rehearsed but oversimplified explanations which fall far short of the definition required to fully explain (and understand) the position that these buildings held in their societies, such as “a castle is the fortified dwelling of a lord”.

In order to see how badly considered such definitions are, we just have to consider the three articles in this particular answer, and ask the following – “What is fortification?”, “What is a dwelling?”, and “What is a lord?” There are no simple answers to these questions, so how can this be a reasonable response?

Again, it has been an approach to suggest that a castle could not exist outside the “feudal system” which has itself been subject to much re-consideration in recent years. Giving a timeframe which is entirely artificial (and anglocentric), suggestions have been made that the period 1066-1485 can act as the boundaries outwith which castles can only rarely be considered “real”. This again is clearly a nonsense, since these dates are driven by the outdated concept of royal dynasties and dynastic change being suitable markers for defining social change. Since these dates refer purely to England, the dates of the Norman Conquest and the end of the Plantagenet dynasty at Bosworth Field, how can they possibly be used to define events outside England?

Over and above this, significant efforts have been made to try to define a castle in linguistic terms, driven by the latin terms castrum and castellum which were in used in medieval documents. In these suggestions, castrum is a fort, and a castellum is the diminutive – a fortlet. From the latter is derived the word “castle”.

However, there are a number of different factors determining what might be considered a castle. It is certainly a high-status building – only those with significant wealth and authority could have them erected. It is certainly a secure building, intended to protect the person and property of the high-status individual responsible for its erection. It serves the purpose of giving a visual representation of the prestige of the person as well – it was intended to look bigger and better than most of those buildings around, without overshadowing the buildings of social superiors. It served as a backdrop for the display of power – the dispensing of patronage and justice, receipt of tendered dues. It served to accommodate the retinue of the individual and their trappings also – in itself a reflection of power. Finally it was one of the – if not the – principal base for that individual. In short, to serve the functions of a castle, such a building had to be big, strong, impressive, luxurious, and multifunctional – and to be associated with a high-status individual or group.

Let’s consider what happens if you omit one or more of these factors.

A high status building without defensive features might be considered to be a manor, mansion or palace, depending on scale. (This is notwithstanding the use of the word “Place” in Scotland interchangeably with palace).

A high status building without high status residential features might be considered a fort or a fortress, again depending on scale.

A high status building not intended to serve the full gamut of social requirements noted above might be a town house, hunting lodge, courthouse, tollhouse or garrison.

A high status defensive structure not dedicated to a single individual or family might be a dun, hillfort, broch, burh, or walled town/city, again depending on scale and date.

It is clear that each of these criteria operates on a sliding scale, and that there are a variety of words that can be applied to buildings and structures serving these various functions. Since these buildings could be primarily built in stone, timber, or a combination of both, and could be built and developed over a timeframe spanning many centuries, there cannot be any architectural features we can consider as definitive. Castles can be provided with and exist without moats, ditches, towers, stone walls, gatehouses, battlements, arrowslits, and so on.

Since we are considering the use of buildings over centuries of social change, it is also the case that a castle cannot be defined by a particular social structure – such as the feudal system (however inherently flawed this term may be). A castle can only be truly defined by the purpose that it held in the society of the time – and therefore cannot be defined by hard boundaries any more than the word “house” can today.

Furthermore, the anglocentric nature of castle studies in Britain is paralleled by insular approaches focussed on Europe. If we were, for example, to consider high status structures in Africa, the Americas and Asia, wherever there is a society that permits high status individuals to erect structures that separate them from their “lessers”, serving the purposes above, there is a type of “lordship” that cannot be defined by Eurocentric feudalism, arbitrary accidents of dynasty, or anything else. Therefore we could find “castles” across the world and in all time periods as an architectural expression of that power. If we consider the defensive aspects of it, we might even consider the island fortress home of Pablo Escobar at Hacienda Nápoles in Colombia a “castle” by any logical definition as an architectural expression of his personal power, wealth and prestige.

This may seem preposterous at first glance, but it is the logical end of the extrapolation process. When there can be

1) no hard boundaries for the functional terms “fortified”, “residence”, “dwelling” or “lordship”,

2) no architectural features which are assigned to castles but no other type of building,

3) no hard datelines which can be used to assign the building type to, and

4) even the word “castle” itself has meant different things to different people through the centuries, and interchangeable with other terms depending upon who was using it,

any definition of a “castle” can only be subjective and varying.

In order to further clarify this, it is helpful to consider a number of examples. Some of these at first glance clearly seem to be “castles”, some not, and others fall into a grey area in between. By considering them in isolation, it should become obvious that the grey area is in fact far larger than one might at first anticipate. As a deliberate decision, these examples are given alphabetically.

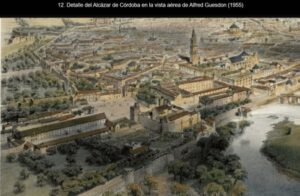

Alcazar of the Caliphs, Cordoba. The Alcazar dates from the 8th to the 11th centuries, and was the seat of government and of the emirs and caliphs of Cordoba; it was also built on top of an older Visigothic fortress. It was then the seat of the Islamic governors until Cordoba was conquered by Ferdinand III of Castile in 1236. It fulfils all the “classic” criteria to be a castle – it was the seat of the lord, it was certainly defensive, it was substantially more impressive then most buildings of the time. However, the area enclosed was very large at about 39,000 square metres, containing streets, mosques, palaces, baths, gardens, and so on – and Islamic society was NOT feudal in nature. The term alcazar is derived from the Arabic al-qasr (itself derived from the latin castrum) and can mean fort, castle or palace, and is often used to describe castles built on earlier fortifications. It is a multi-functional name. In Cordoba part of the Alcazar of the Caliphs formed the basis of the Alcazar de los Reyes Cristianos, started by Alfonso XI in 1328. Part of this structure was a squarish courtyard with corner towers – but his Alcazar retained gardens, baths and other features from the older building. The questions that have to be asked are these – at what point in time did the Alcazar suddenly change function to become a castle rather than anything else, what part of the Alcazar was a castle if all of it was not, and what was it if it was not a castle?

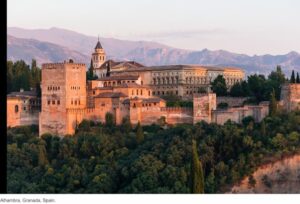

Alhambra, Granada. The Alhambra was also built on the site of a Visigothic fortress from the 9th century, and a defensive structure was maintained here through to the 13th century. When Cordoba fell, Ibn al-Ahmar established the emirate of Granada and started work on a new castle called the Alhambra in 1238. The castle then developed into a palace-city occupying a substantial area of about 142,000 square metres, with the Alcazaba at the western end. Further palaces, gardens and courts were added into the 15th century. When Granada surrendered to Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile in 1492, the last sultan removed the bodies of his ancestors from the Alhambra, and the buildings became one of the principal palace fortresses of the Spanish crown. The same questions have to be asked about the Alhambra as the Alcazar at Cordoba, but it needs to be borne in mind that the Alhambra was entirely devoted to be a high status area, so there is no question of considering it as a settlement in any way.

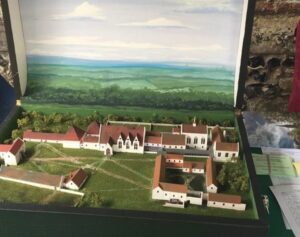

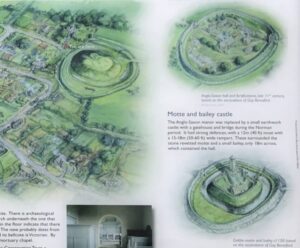

Altyre “earthwork”, Moray. This is a relatively modest sized subcircular mound of earth adjacent to a 13th century chapel and a minor watercourse. The mound is perhaps five metres tall and has a summit area perhaps 15 metres across, therefore can be considered mid-size in terms of Scottish mottes. The summit area was probably protected by a timber palisade and may have had one or two halls upon it. There is no evidence of a ditch surrounding the mound, and a winding path can be traced around part of the slopes which may represent an approach track or be a later landscaping feature. It is consistent with being constructed in the 12th century, and may have been used as a hunting seat by the king as Altyre was royal forest. In the context of Moray, the structure is dominant in the landscape, larger than contemporary houses, defensive in nature, and occupied periodically by the king. His officers used it and maintained it in his absence, and royal forest is of itself an expression of lordship, so the structure at Altyre does fulfil the criteria of being a castle. A stone tower was later built on the top of the mound, but the nature of this is not known as it is only shown in a single woodcut from the 18th century.

Ardoch fort, near Perth. Ardoch is a Roman fort, occupied periodically for perhaps a century or more in the first and second centuries AD. It was intended to be a permanent structure, and was occupied by Roman legionaries. Consisting of a stone-walled courtyard with defensive towers and gateways, it was surrounded by several consecutive sets of ditches. It was of course primarily military in function. However it was a direct representation of Imperial rule in Britannia, would have been the local point for collection of taxes, and whilst the Emperor himself might never visit, his deputy the governor may well have done so on occasion, and the fort commander was resident, potentially with trappings of Empire like a temple, baths, and so on. It was an impressive structure in the landscape, certainly far grander and more complex than any native British structure nearby. Were we to take away knowledge such as the date of occupation, and leave just the buildings and defences standing, we would have no problem identifying this as a castle.

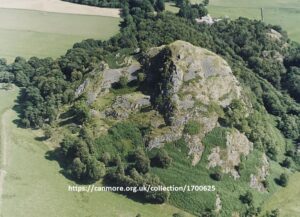

Bass of Inverurie, Aberdeenshire. This was another earth and timber structure, but of a different model to that at Altyre. Built by Earl David of Huntingdon as the seat of his lordship of Garioch in the 12th century, it has two main components, unhelpfully “sculpted” in the 19th century during landscaping works in the burial ground that it now sits. There are two enclosures, an upper and lower, with the upper one at the top of a conical “motte” and the lower sitting adjacent. The two mounds are separated by a ditch that is 19th century in origin, and were surrounded by a ditch and bank that have now been removed. The top of the upper mound is small, only wide enough to house a single timber watchtower, and the lower is larger, but still only able to house a couple of timber hall-type buildings. As it has a known history, we can state that it served as the seat of a lord, was representative of his lordship, and it was significantly larger than other residences nearby. It is likely that timber palisades atop the mounds provided defence, but was it the residence of the lord? That is questionable since Earl David was a cosmopolitan prince, heir to the Scottish throne, a crusader, and held one of the wealthier English earldoms. In a time when his compatriots south of the border were building massive stone keeps (and we know that David had more than one of these himself) one has to wonder whether it was built to serve his principal officers in Garioch.

Bodiam Castle, Sussex. This is one of the best known and most photographed castles in England. It was founded for a knight of Edward III in 1385. He was a younger son who had made his fortune in France at war, and elected to build the castle on a platform within a wide moat. The courtyard is roughly square shaped, with towers at each corner and midway down each side, except for that containing the gatehouse. Inside there were ranges of buildings around all four sides arranged in a manner usually followed by the great houses of the time. When built it was undoubtedly an impressive building, the lord was resident, and within the moat it is clearly defensive. The question is simple though. Was it actually built for defence, or was it actually a castellated house built primarily for display – who was it intended to defend against? Image below is from Wikipedia, reproduced under creative commons license original owner Wyrdlight.

Boyne Palace, Banffshire. To a certain extent, Boyne Palace may be considered a more extreme example of deliberate archaism than Bodiam. Built for the Ogilvie family in the 16th century, it too has a quadrangular design, with round towers at the corners, a twin towered gatehouse, and a great hall on one side. It too has a wide moat, although it is dry and crossed by a causeway. However the walls are too thin to offer serious defence against assault, the castle is provided with gun loops, and the only likely enemies to attack were fellow Scots. Serious assault was not anticipated. Apart from a couple of centuries, Boyne Palace seems to serve the same purpose as Bodiam – lordly display which was all about pomp.

Castlehill of Strachan, Aberdeenshire. This is a small mound which once housed a single hall on the summit. Smaller than either Altyre of the Bass of Inverurie, the mound was intended to serve two purposes. One was defensive – the mound was actually surrounded by a complex of drainage dikes which allowed a small number of enclosed spaces to be used for farming. The other was status – by raising the little hall up, it could be seen for a distance around. It was intended to serve the purposes of a castle by its lords. Yet the hall was modest, the walls bowed out like the sides of a boat, and although there was at least two separate palisades erected around the edge of the mound, the space was restricted and the mound unstable, one of the phases appears to have ended in subsidence, the other in fire.

Château de Doué-la-Fontaine, Anjou . This structure is believed to have been built for the Count of Anjou, in about 950AD. The stone built hall of the castle was built on top of an earlier hall, measuring 23 metres by 17, with walls about 1.80 metres thick. A mound was built up around the basement of the hall that was five metres high, and a stone keep built on top, the hall becoming a cellar. The question here is to consider at what point the substantial hall, which was presumably not a standalone structure, could be considered a castle. As it was presumably surrounded by a courtyard of some description – even if this was defined solely by a palisade – was it a castle at its inception? Or was it the addition of the mound and raising in height? The functions of the building remained the same – and despite comments that it had a bailey, no evidence of this is known.

Clarendon Palace, Salisbury. Clarendon Palace is one of a number of royal palaces erected in England for the Plantagenet kings. Containing all the appropriate high-status buildings that the royal household required, the buildings here were of the highest passible quality, and therefore were a visual representation of the royal power and authority. It was regularly occupied by the royal households into the 15th century. The only aspect that appears to be lacking is that of defence. Could Clarendon be considered a castle without it? On closer examination, it is clear that there was a boundary wall surrounding the complex in the form of a wall and defensive bank and ditch. Although these may have served a largely symbolic function, these may in medieval times have been a more substantial defence than we believe today, since the security of the monarch was a serious matter.

Craigievar Castle, Aberdeenshire. Craigievar is an early 17th century tower house completed for the Forbes family, and probably incorporating an earlier tower. It was originally provided with a walled courtyard, and despite its fanciful decoration, it was intended as a defensive structure. However it was unfinished when the Forbes family purchased it in 1610, and not finished until 1625 or 1626. By this time, fashion had changed, Scotland was no longer at war with England, and the tower became an expression of the wealth of the Forbes lairds. Again the question comes to whether the tower was functional as a defensive structure – or whether it was just about display. It would not have been possible in the 1620s to foresee the onset of the Civil War – and against an army provided with artillery Craigievar was not well defensive at all.

Crathie Point promontory fort, Banffshire. This is a promontory fort occupying a coastal clifftop site. Defended by earthworks separating the promontory from the mainland, (two ditches with ramparts creating two courtyard areas) it was occupied in the early Iron Age, and at least one of the banks was topped with a timber palisade. In form it is similar defensively to the earthworks of medieval fortified promontories, and prior to the creation of the stone courtyards and towers it is feasible that the earlier phases of these castles would be difficult to separate from Iron Age forts like Crathie Point. The purpose of Crathie Point was clearly defensive, and it is likely that the community who lived beyond was small in number, regardless of whether both defences were in use at the same time. Being defensive, containing a degree of status, and able to project an aura of strength and power, it is likely that a chief of some description could have been considered a lord when it was occupied. Certainly we might expect a high status residence within.

Diocletian’s palace at Split in Croatia was built in the early 4th century when the Roman Emperor Diocletian resigned his post and retired. The building was quadrangular, was provided with three massive double towered gatehouses on three sides (the fourth faced the sea), corner towers, and on the landward facing sides towers between the corners and gatehouses. The emperor’s apartments were spaced along the sea wall, the remaining area was divided into four unequal quarters. The scale of the building was clearly palatial and a massive display of wealth and power. The walls, towers and gates made it substantial fortification, and although he had retired, Diocletian remained a monarch – a lord – and this was his residence. Measuring about 200 metres a side, the palace could be considered a castle on a massive scale.

Dun Laghaidh, Wester Ross. This fortified site occupies a hilltop location, and was occupied in several phases spanning centuries. The earliest phase was a timber-laced fort, conceived as a single wall enclosing the hilltop. The enclosed space was perhaps 85 metres by 25, with a secondary wall defending the gate. There was space inside for a small community to have lived or the household of a local lord of some description plus his warband. This was carbon dated to perhaps 550BCE. On the eastern half of the fort, a dun was then built, consisting of a single wall, about four metres thick. A mural stair led to the wallwalk, and the entrance gateway was provided with a guard chamber and two doors. In the 12th century the dun was converted for reuse. The entrance was blocked, the wall strengthened and the mural stair became the entrance. A small area of the courtyard outside the dun was then enclosed with walls joining the old fort wall. A small hoard of late 12th/early 13th century coins was found on site. Both the dun and the medieval occupation are indicative of a local lord expressing his power here and we return to the question of assessing when this site could be assessed as a castle from, since all the relevant criteria are filled in all phases of occupation.

Dundurn, Perthshire. Dundurn is an impressive structure built on an isolated rocky crag in the valley of the Earn. Defended by a series of walls enclosing courtyards all around the crag, it was occupied in the 7th century AD, and eventually abandoned in the 10th or 11th century. At the summit was a round dun-like structure that was almost certainly the high status residence of the local king. The location was totally dominant in the landscape, the repeated walled courtyards on the ascent to the summit is clearly very defensive, and it is pretty clear that the place was the residence of a powerful lord or local king of the Picts. The great roundhouse or dun at the top was his residence and was of greater stature than other houses in the vicinity, and therefore was an architectural expression of power and lordship.

Goltho, Lincolnshire. In about 850AD, a defensive bank and ditch were erected around a group of domestic buildings including a hall. This was later rebuilt within the exiting defences, and then rebuilt a second time, this time with the defences enlarged and strengthened. Sometime between 1080 and 1150, a small motte was then erected within the enclosure, before being levelled and rebuilt to a new design. This is a good example of a thegnly residence predating the Norman Conquest, and fulfils all the criteria of a castle. However, it is only with the addition of the motte that Goltho is considered to have become a castle. Why is that?

Great Enclosure, Great Zimbabwe. The great Enclosure is a substantial walled enclosure within the stone city of Great Zimbabwe. The main walls measure up to eleven metres tall and enclose an area about 250 metres across; there are also smaller external stone walls. Within the enclosure is the Conical Tower, which measures about 5.5 metres across and 9 metres high. It was occupied from the 13th to 15th centuries. The history of the site is still being researched and is difficult to establish for political reasons. However it is possible to consider that the Great Enclosure may have served castle-like functions.

Harlech Castle, Sir Meirionydd. I know, who in their right mind would question whether Harlech is a castle? It would appear to be obvious. However, the question boils down to the definition of residence and lordship. Harlech is clearly a high status and very impressive defensive building. The gatehouse contained residential suites and the castle was intended to broadcast the conquest of Wales by Edward I as well as serve as an administrative centre for his new county of Meirionydd. However, it is unlikely that the king ever intended to reside there regularly. Whilst his officer was present, and his soldiers were present, Harlech could be argued to serve the same function as Ardoch Roman fort. A high status garrisoned fort, with deputies exercising the lordship on behalf of the lord.

Krak des Chevaliers, Syria. Again, this would appear at first glance to be an unusual site to include. However Krak des Chevaliers was rebuilt by the Knights Hospitaller in the 1140s, and occupied by them until 1271 when it was captured by the Sultan Baybars. Again, the question is one of lordship and residence. The Knights Hospitaller were an increasingly military order of soldier monks whose original purpose was to care for and protect pilgrims to the Holy Land. Their purpose meant that exercising and displaying lordship was not relevant. Clearly Krak was a very well developed and impressive defensive structure, and at its peak there were perhaps 2,000 knights present at the site. But who was the lord? Was he resident? The answer to that is simple. The Grand Master of the Order was the lord – but only as a representative of the church. Donations made the order wealthy and able to build structures like Krak to operate from. But they were functionally fortified monasteries. The Grand Master had no primary residence – the Order had vast estates. Without the exercise of lordship or the presence of a lord, how can it be a castle?

Mains of Drummuir, Banffshire. The Mains of Drummuir is a defended house dating to the 17th century. It is built on a slope and the entrance to the house today is on the first floor. The approach to the old doorway is protected by shot holes, and this door has drawbar holes demonstrating a need for security. As a “laird’s house” it is of higher status and greater size than most properties were at the time, and although the windows now are larger than they once were, it would have been quite hard to force access. It was, to be honest, a strong farm house. However. The main gunloop is of a high-status triple hole design and one of the window pediments is monogrammed. There was an element of display here, and that means on some level the laird wanted people to see his residence and be impressed. It may not look like a castle – but it certainly ticks the boxes. It is just the scale of the reworked building that is troublesome.

Malbork, Poland. As with Krak des Chevaliers, Malbork was a structure erected by a military Order of knights – the Teutonic knights. It was built after 1274 in order to act as a head quarters for the Order to enable them to consolidate the conquest of Old Prussia. From 1308 it became the administrative centre of the Order. The complex is massive, the developed area covering more than 44 acres, and there was once 3,000 knights housed here. In comparison to Krak in Syria, this was the seat of the Order and the Grand Master was resident here – at least until the Order went bankrupt. After this, it became a royal fortress held by the kings of Poland. However, was the Grand Master the lord, or was the Order? Was the church? And, as with the case with other massive sites, like the Spanish sites above, at what point did it become a castle – or was only part of it ever a castle?

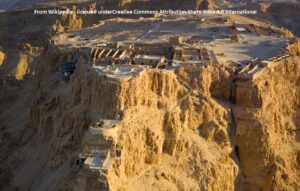

Masada, Israel. Realistically I could have picked one of a number of Herod the Great’s buildings, but Masada is the most famous. Built in the early 1st century AD by the King of Judaea, Masada occupies a massive outcrop of rock in the desert, and is pretty impregnable unless you have the resources of an Empire to draw on. The main defence is a massive stone wall enclosing the summit of the hill, but at one end was a luxurious palace dropping down several steps. The summit contained granaries, storehouses, lower status accommodation and other trappings of royalty, and overall the site is designed to impress and provide a safe place for an increasingly troubled king to live. It fulfils all the criteria of a castle. But the challenge is one of scale and identifying the nature of the castle. The palace is unfortified except for the sheer rock face – and in fact as it is overlooked by the summit, it is not at all defensive. So, despite the fact that Masada was clearly the fortified residence of a lord, was it in fact a combination of a palace and a fort, or can it be considered as a single architectural structure?

Mote Hill, Tillydrone Aberdeen. At the top of a river cliff, the mote hill is a conical mound with a summit area measuring nine metres by five. It is between five and seven metres high, and was surrounded by a ditch, Excavation revealed a stone revetment at the base, and evidence of palisades. Up until carbon dating demonstrated the site was a Bronze Age burial mound reused in the Iron Age (dated mid 2nd century AD) this was firmly believed to be a motte. NO evidence of medieval use has been found, but everything points towards it serving the same function at the time – and having all the medieval architectural features.

Nybster Broch, Caithness. This circular roundhouse was built behind an existing fortified promontory with a possible ditch, and a defensive wall. It was occupied in the 2nd century AD, and was the first building a visitor would encounter behind the timber-laced rampart isolating the complex. The rampart had timber doors blocking access, and mural stairs led to a wallwalk. Behind the tower and occupying the remainder of the promontory is a complex of buildings that is broadly contemporary, and many of which are small round cellular buildings. In principal the design here is similar to fortified promontories like Forse Castle, and whilst the society of the broch-builders is a matter of debate, why should we not consider this a castle?

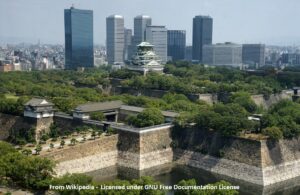

Osaka Castle, Japan. Work on Osaka Castle started in 1583, and it was a conscious imitation of the castle at Azuki, erected by the Nobunaga clan. The lord, Toyotomi Hideyoshi intended to surpass it in every way. The structure is undoubtedly impressive in scale, and functionally defensive as it held off an assault from Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1614 – who had an army of 200,000 men – although it did fall to them later. It was the Tokugawa clan who then started to rebuild, including the main “keep” complex on raised platforms of rock incorporating wet and dry moats. This has eight storeys, three of which are subterranean. Samurai society was feudal in nature, and both the Toyotomi and Tokugawa were part of the ruling military class. Samurai castles were intended to serve all the same functions as castles in other parts of the world, but were built with fortified towns as a fundamental part of them, and served many functions including symbolic ones. Where did the castle end if the inner “rings” of towns were consciously high status?

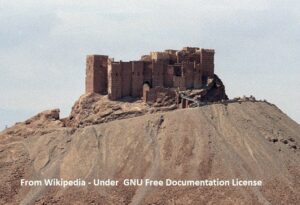

Palmyra Castle, Syria. Palmyra Castle is a 13th century fortification erected by the Mamluks, the military class who dominated the area in the 13th century. Built on top of a hill, with a moat, it overlooks the sadly decimated World Heritage Site of Palmyra, and was partially blown up by ISIS forces on their retreat. One might say that by any standard, this is a castle. Built in four phases, the earliest was a triangular courtyard with eight rectangular towers. A second courtyard area was enclosed with a further five towers just down the south-eastern slope, a third on the west side with three towers; this was subsequently extended with a further two towers. However, in contrast to other citadels of the time, there is no bath house, no palace, no gardens, no mosque. This removes the possibility that it was ever residential, and it is believed it served purely military and policing functions. As such, can we consider it to be a castle?

Qasr Kharana, Jordan. The building is square, measuring 35 metres a side, with corner towers and a formal gate entrance. Built in the 8th century near an important road, it was intended as a symbol of the lordship of the caliph Walid I, and the layout follows a domestic design with public and private areas of accommodation. High status, impressive, dominant, and offering accommodation of a suitable quality, it does appear to be a castle, and is often considered as one. However, what practical assertions of dominance were carried out here? It is questionable as to whether this was the case, or whether Walid intended to have the place as a very strong overnight residence to stay in when passing through.

Queenborough Castle, Kent. Queenborough was built for Edward III in Kent, possibly modelled on Bellver Castle in Majllorca, itself perhaps following the plan of Herod the Great’s fortress palace at Herodium. It was designed to respond to the increase in importance of artillery in warfare, and the central buildings formed the archetype for the artillery forts of Henry VIII, although much taller. The outer court was a circular walled courtyard without towers, just a twin towered gatehouse, and was circular, surrounded by a wet moat. Although the central complex contained perhaps fifty rooms, and the castle was named after his queen, it has to be questioned exactly how much time was intended to be spent here by the king and his family. Unfortunately evidence is scant, and it has to be asked whether Queenborough was actually a fort rather than a castle.

Ravenscraig Castle, Fife. Ravenscraig is another castle where artillery had a definite role to play. Founded at the instruction of James II in 1460, it was unfinished when granted to the Sinclair family as part of a deal whereby they became earls of Caithness rather than Orkney. The outer fortifications consist of two massive D-plan towers connected by a central block, all behind a massive ditch. Behind this is a narrow suite of accommodation extending out onto the promontory behind. The question has to be asked here as to whether there was ever any intention for there to be a lords residence at Ravenscraig, or whether it was always intended to serve a purely military function. Given that the defences face outwards, with little attempt to defend from a sea-borne attack, the jury has to be out here as to the military function as well. Who was it defending against? Or was it all about status?

Spynie Palace, Moray. This site is a particular bugbear of mine. Containing the largest tower house by volume in all of Scotland, and consisting of a walled courtyard with corner towers and a twin-towered gatehouse, it was the residence of the Bishops of Moray from the 13th century at least. It is high status, served as the seat of the lay barony held by the bishops in terms of justice and tithes, and in every way it is a castle. And yet, it is known as the palace of Spynie – and I got banned from a Facebook group for sharing a post about it where I considered it a castle. It does not possess the attributes of a palace as it is clearly defensive in nature – and represents the difficulty of using words to determine the nature of a building.

Ringwork and bailey, St Davids, Pembrokeshire. This is an impressive earth and timber castle built just outside St Davids in Pembrokeshire. Defended by ditches, banks, and palisades, it was here that William the Conqueror based himself when visiting the area. It was here that he would have held state and received the homage of native Welsh lords. However, as it lay within the lands of the bishop, it was built just for this visit, and is unlikely to have ever been used again unless for the occasional visit of the Kings of England to the area. As such can it be categorised a castle since it was only ever a temporary occupancy?

Stokesay Castle, Shropshire. This is often categorised as a fortified manor, built in the 13th century. Consisting of a pair of halls between two towers, and an associated walled courtyard with a gatehouse, and surrounded by a ditch, it served as a seat of lordship from its first construction. It was intended to serve as a defensive home for the builder, Laurence of Ludlow, and was of notably higher status and size than most of the buildings nearby. However, it was built in stages, and it may be that the great tower to the south was the result of a license to crenellate issued in 1291. Stokesay does seem to fulfil the criteria to be considered a castle, and the only possible concern would be to consider exactly how defensive it actually was, which is a very subjective matter.

Tap O Noth, Aberdeenshire. This is an impressive hill which is crowned by a massive stone wall enclosing an area of about 100 metres by 30. A second rampart was constructed lower down the hill in the 5th or 6th century AD, at which point there may have been as many as 800 houses here. The walled enclosure is certainly primitive and massive, and there were one or two large roundhouses within as well as a cistern. There is no gate opening surviving, so presumably this was at a raised level that has since collapsed. If, as seems possible, this was the “citadel” within a larger settlement, it might be considered a castle according to the criteria given, although there is always a possible ceremonial aspect to consider.

Tattershall Castle, Lincolnshire. The castle at Tattershall is justifiably famous because of its impressive brick-built tower dating from the 15th century. Previously a stone built courtyard castle, the foundations of some parts of which survive, Lord Cromwell’s construction was a declaration of his wealth and power. As such, the defensive qualities of the castle were secondary to the matters of display, and although the moats from the 13th century castle survive, they were not considered “good enough” for Lord Cromwell, and he upgraded just about everything he could lay his hands on. Stylistically, Tattershall is a castle, of course. But it was built at a time when defence was taking a back seat, and I wonder if there is an argument for suggesting that it sits in a grey area between castle and palace.

The Rings, Corfe, Dorset. The Rings is a siege castle dating from the 12th century, when forces loyal to King Stephen and others loyal to the Empress Matilda fought over which party they felt ought to be King/Queen of England. In 1139, King Stephen attempted to besiege Corfe Castle and had a ringwork and bailey constructed to act as the field HQ. The siege was unsuccessful, and Stephen was forced to withdraw; the Rings were never used again in the medieval period. Although King Stephen was probably personally resident at the Rings, there is unlikely to have been anything high status built here reflecting this, and he may have actually been living in a (rather large) tent. Since there was a purely military function, can we consider the Rings to have been the residence of a lord? I’m not sure.

Trelleborg, Denmark. This is a massive circular earthwork with four openings, within which were a number of great timber halls. It was erected along with a number of other structures at the same time for King Haraldr Bluetooth of Denmark circa 980 AD. The earthwork is a massive bank within a ditch, originally encased in near-vertical oak timbers and outside this is an irregular area also defended by a bank and ditch, although on a smaller scale. Trelleborg is interpreted as a fortress, and there is no evidence to suggest the residential aspect of what a castle can be defined as, but as King Haraldr was a soldier king, it is possible to suggest that he would have spend time here with the hundreds of men who could be housed within the rampart. Since the outer ward contained buildings believed to have been stables, workshops and the like, this was more than just a military garrison, and although Trelleborg was only occupied for about 10-15 years, one might consider that there were aspects of the structure that could be interpreted as serving many of the functions of a castle.

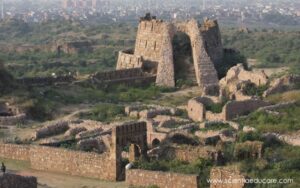

Tughlaqabad Citadel, Delhi. There are parallels to be drawn between the structures of Tughlaqabad and the Spanish complexes mentioned above. There is a fortified city and a palace area where royal residences were to be found, and a citadel. This latter part contains defensive walls with bastions, a mosque, a palace, and defended gates. It was intended to defend the sultan, who could be in residence. Massively impressive, it was unquestionably a castle. However one has to consider where the castle actually stopped as the integrated defences extend to protect other parts of the complex. One can only access the citadel from the palace area, for example.

Varrich/Ardclach. These two towers are in the far north of Scotland and Moray respectively. Both appear to be small isolated towers, although they are of different dates. Neither have outworks that can be identified, and both are small in scale. However, they are defensive in nature, they are placed in highly visible locations that dominate the landscape even of the towers themselves do not, and therefore are intended to project power in some form, however limited. As castles, they are smaller than might normally be accepted, and perhaps were not intended to be permanently occupied. However, the date of Varrich is disputed and it was probably repaired on more than one occasion – so we do not actually know what it was for or who built it, and it may be that it formed part of a lost high status complex where the lord in question occupied a timber hall. Ardclach is known as a bell tower because it has a bell, and is considered to have been used to warn locals of raids, or to summon people to church. Both these suggestions are problematical as reasons for building the tower in the first place, although it undoubtedly served this purpose in the 17th century. If they are to be discounted as castles, why should we include other standalone towers of slightly larger scale? There is always a sliding scale with these things, and it is hard to identify a specific line objectively.

Y Pigwn Roman Marching camp. Unlike Ardoch fort, the marching camp(s) at Y Pigwn in Carmarthenshire were not intended to be occupied permanently. However, it is also the case that the Roman army, representative of Empire, and with the Imperial representative at the head of his army, occupied marching camps for lengths of time far greater than used to be believed – excavations near Kintore in Aberdeenshire show that three months might be anticipated. As dominant features in the landscape, intended to defend the soldiers and dominate the locals, far more massive in scale, they do tick some boxes. Added to which they were occupied by the “lord” who was there to dominate and exploit the area for a period of time longer than, say, William the Conqueror was at St Davids, or one of the Norman lords was present at a siege castle. Should they not be considered castles?

I have here deliberately not included any sites from the Americas. This is because the history of pre-Columbian society in the Americas is extremely troublesome. During the centuries of the “High Medieval” and early Renaissance period in Europe, the Americas did have large quasi-imperial political entities which had substantial settlements scattered across their territory. Within some of these settlements were massive structures such as the pyramids at Teotihuacan, the temples of the Maya at Chichen Itza and Tikal, the temples of the Aztecs at Tenochtitlan, the Casa Grande Ruins of the Hohokam in Arizona, the Cahokia earthworks of the Mississippian culture in Illinois and so on. Within these settlements there were undoubtedly high status residences for the ruling classes. It is conceivable that some were defensive in nature. However, so little has survived of these cultures in terms of understanding how they worked that it is not really possible to ascertain which structures were religious and which secular in function – or even if there was a substantive difference between the two. The post Columbian conquest of the Americas and the wholesale destruction of the societies there was accompanied by a vicious apartheid that suppressed much of what we would find useful to understand them.

I have also deliberately omitted sites erected by the ancient Egyptians for the same reason. Pharaoh was king and god both, and owned the entirety of Egypt outright. As such, there is little actual lordship. Whilst there are substantial fortresses known from the 2nd millennium BCE, these were exclusively military structures and Pharaoh did not reside in them. Without high status residential function, these cannot have served as castles.

To a certain extent, some of these choices have been made with tongue in cheek. However, they do serve to illustrate that the question of defining a caste is nowhere near as simple as might be thought – and even current definitions as put forward by academics do not successfully fulfil the remit. In order to define anything there has to be a boundary. Either something is, or something is not, a “thing” in question. There can be no grey areas. And that, fundamentally, is the problem. A castle is a building that served multiple functions, had no universal architectural features, and was erected for people of varying status over varying timeframes within which societies changed radically, as did the technology they used.

How can we define any of the criteria within hard boundaries, when the criteria themselves are so subjective? Where does “defensive” stop, and “fortified” start? What defines a “lord” or the nature of his “lordship” – and how does that differ from serving a greater “lord”? How long does a place need to be “occupied” by an individual before they are said to “reside” there?

I do not think it is possible to provide a concise definition for a type of building that has existed for millennia and served so many functions. To attempt to do so is to restrict buildings that fall outside a narrow focus, and ultimately fails to appreciate the full scale of how they were used, and why they were built – and in turn fails to understand them and limits their study. One cannot dissociate a castle from the men, women and children that lived, worked, and died in them, because it is those people who provide the context for the building’s existence. A single castle can not be understood in purely architectural terms, purely military terms, purely social terms, but only in the totality of its existence through the time that it was used. Palmyra Castle, for example, was damaged by ISIS when they withdrew soldiers from it that had been occupying it during a war in 2016. As such, it still had military relevance within their particular context (however repugnant). It is perhaps relevant to note that as Palmyra was a military structure in the medieval period, it also served a purely military function a few years ago.

If a concise definition is not possible, is a broad definition possible – or even desirable? The more narrow the criteria provided, then the fewer sites can be defined within those criteria. For some, that may be desirable, but I do not believe so. So I return to the start of this paper, and would like to adjust the definition slightly. A castle was a high status structure, the architecture of which provided security for a high status individual when they were occupying it, and segregating that individual from the general population. At the smaller end of the scale we have buildings with defensive features built in, and a display perhaps best interpreted as pretensions of power. At the other end of the scale we have truly gigantic structures built within, or in association with, cities. Built from antiquity into the modern age, castles could perhaps best be described as architecture of power.

Before I close, and leave readers with an idea that somehow castles were the shoulder padded jackets and Filofaxes of the past, I have one further question to offer. Under what circumstances have castles – or buildings serving those purposes – NOT existed?