Maryport, Cockermouth and Egremont, Scottish castles in England?

As I outlined in my Castle Guide for Edinburgh, and in my essay about the historical MacBeth, the history of Scotland below the Forth-Clyde isthmus is rather more complicated than we are generally led to believe. After the withdrawal of the Roman legions in the 5th century, the north-east was settled by Angles from the area of the modern German/Danish border, and who became the dominant culture over the British tribes who had lived there previously.

The Anglian kingdoms which arose from this process included Bernicia, stretching from the Forth to the Tees, which shared a border with the southern Picts at the Forth, and the British people of Strathclyde and Cumbria. It is not known exactly where this latter border lay, but it is likely that a vaguely demarcated military zone lay between Edinburgh and Stirling into Ettrick Forest, and a similar vague zone occupied the hills southwards towards the Yorkshire Dales.

At some point in the early 11th century, Strathclyde finally fell under the dominance of the kings of Scots. The last record of a separate king of Strathclyde is in 1035, but it is equally possible that he was the subordinate of the Scottish king, and that his descendants ruled after him for some decades. It should be noted that the title of Owen was King of the Cumbrians – and not King of Strathclyde, which is the modern terminology.

The north-west of what is now England was known as the Kingdom of Rheged, which probably passed to Anglian rule in the late 7th or early 8th century. It is likely that at times the authority of the kings of Rheged spread south into Lancashire, east into Yorkshire, and along the north Solway coast into Galloway. It subsequently became part of the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria, until that kingdom fell to the Dames in the 10th century. It is believed that parts of the north-west – most likely the coastal regions of Cumbria and the fertile lands around the old regional capital of Carlisle subsequently passed under the authority of the kingdom of Strathclyde.

In my essay on the historical MacBeth, I demonstrated that Scotland and Northumbria had a somewhat fractious relationship. One of the principal reasons given for the downfall of King Duncan was his invasion of Northumbria and defeat at Durham in about 1040. I also highlighted that his younger brother Maldred is believed to have been given a position of authority in Cumbria, particularly the region known as Allerdale, and had married into the dispossessed native dynasty of Bernicia (ousted by Canute and replaced with Siward). Maldred was killed fighting MacBeth of Scotland c1045, leaving two sons, Malcolm and Gospatrick.

It is recorded that shortly after this event Siward led an invasion which resulted in MacBeths defeat, and the installation of Malcolm, son of the King of the Cumbrians in his place. It seems likely to me that this was Malcolm son of Maldred, and that he was placed in control of the territory around modern day Cumbria since MacBeth carried on as King of Scots until 1057! What happened to this Malcolm afterwards is not known. However he does not appear to have had any children to take over Cumbria, and by 1066 his brother Gospatrick was ruling the area.

In 1067, Gospatrick was made Earl of Northumberland by King William I of England, probably leaving a younger brother Dolfin to rule Cumberland. Gospatrick was involved in the rebellion of the north in 1068, and was dispossessed, but returned to be Earl from 1070-72, when he was exiled and fled to Scotland, and was granted lands centred on Dunbar. His son Waltheof replaced him from 1072-1075, when he was executed. Northumbria was granted to the Bishop of Durham (murdered during rebellion in 1080), Aubrey de Coucy (possibly forfeited 1086, returned to France), and Robert de Mowbray (rebelled and imprisoned for life in 1095) before it was taken back by William II.

Dolfin of Cumberland (or possibly his nephew of the same name) was considered a problem by William II of England, who expelled him from Cumberland with a great army in 1092. Cumberland was then formally broken up into large baronies, including Allerdale above Derwent, later known as the Barony of Egremont, and Allerdale below Derwent, later known for ease as the Barony of Allerdale.

The lion’s share of these lands were granted to Ranulf de Meschin, (including Carlisle and the lands which would come to be known as Copeland) while some were granted to his younger brother William (the lands which would come to be known as Allerdale).

At this point, Scotland dissolved into civil war. King Malcolm III and his designated heir Edward, were killed in 1093 at the same battle during an invasion of Northumberland. Malcolm’s brother Donald seized the throne, and fought against the sons of Malcolm to keep it. Delighted to interfere, King William II gave support to Prince Duncan, who took the throne with Northumbrian support in the form of an army.

Duncan had been a hostage at the court of William the Conqueror from 1072, and was married to Uhtreda, a daughter of Earl Gospatrick, by whom he had a son, known as William fitzDuncan. He had been a member of the English royal court of William II from 1087, so perhaps the choice of his son’s name reflects his debt of gratitude to the English king. However, Duncan’s army of occupation was unpopular in Scotland, and he was forced to send them away, giving his uncle the former king Donald, and half-brother Edmund a chance to depose, and dispose of him in 1094. It is likely that young William fitzDuncan fled Scotland at this time. In Scotland, prince Edgar recruited English aid to take the throne from his uncle Donald in 1095, and ruled until 1107.

William de Meschin was married to Cecily de Romely, heiress daughter of the Lord of Skipton in Yorkshire. Copeland was retained by William de Meschin until his death perhaps around 1135, and after the death of his heir Ranulf fitzWilliam at around the same time, it became the property of his heiress daughter Alice, along with Skipton. The rest of his estates were split among two further daughters.

After the elder Ranulf had been permitted to inherit the earldom of Chester, he resigned all his lands in Cumberland to the Crown as part of the deal. Carlisle was retained by King Henry, with its important castle, whilst Allerdale was granted by the King to Waltheof, a younger son of the exiled Gospatrick of Dunbar, and who remained Lord of this territory until 1138.

Waltheof of Allerdale and his brother Gospatrick (II) Earl of Dunbar both died in this year. Childless, he was followed by his younger brother Alexander I. During Alexander’s reign, and probably with the influence of King Henry I of England, Alexander’s younger brother David was appointed to look after southern Scotland, and was referred to as “Prince of the Cumbrians” from at least 1113 to 1124, when Alexander died.

The title did not refer to English Cumberland, however, and David’s lands appear to have consisted of most of Scotland south of the Forth, stretching westwards to include the lands as far as the Clyde valley. David’s wife was the daughter of Earl Waltheof of Northumberland (executed 1075) – a territory which had included Westmorland and Cumberland as well as the temporalities of the Bishopric of Durham.

This gave David a claim to vast lands in northern England, but King Henry, perhaps aware by this time of a distinct possibility that David would be the next King of Scots, was not to grant him the domination over vast lands in the area. Instead, as we have seen, when Ranulf de Meschin surrendered Carlisle and Westmorland to Henry in 1120, that king kept it as a royal estate, and strengthened the castle. Northumberland also remained in the hands of King Henry for the rest of his reign, meaning that the claim of David’s wife was limited to set estates within the former earldom.

After the death of Henry I, England descended into civil war, with the famous Anarchy of Stephen and Matilda’s reign. This enabled King David of Scotland to occupy and dominate much of northern England, seizing castles from Carlisle to Newcastle in early 1136. He was in a sufficiently strong position to insist that his son Henry was appointed given half the lands of the old earldom of Northumberland, and have himself appointed lord of Carlisle. After Henry was treated badly at Stephen’s court, David invaded again, leading to a truce, and a third time in early 1138. In this third invasion, William fitzDuncan defeated a force of English at Clitheroe.

It is not clear where William fitzDuncan had been living all this time. He may have been appointed as Earl of Moray by David after the defeat of the rebel Earl Angus in 1130, but he also became a lord of some significance in England in the 1130s. We have seen that Alice de Meschin had become Lady of Copeland & Skipton after the death of her father between 1130 and 1135 – and her husband was William fitzDuncan. Wiliam’s mother, Uhtreda was one of the daughters of the exiled Earl Gospatrick of Northumbria, and after the death of Waltheof of Allerdale in 1138, the claim to Allerdale also passed through her to William.

So, by 1140, William fitzDuncan was Earl of Moray (possibly), Lord of Allerdale, Lord of Skipton in Craven, and acting Lord of Copeland. He was also – after the son of King David – second in line to be King of Scots. For such a prominent member of the Scots nobility, he controlled a substantial proportion of northern England. The boundary of Allerdale and Copeland ran from the northern shore of Moricombe Bay on the Solway Firth to include Wigton and Keswick, down to Broughton in Furness. The boundary between the two was the River Derwent from the coast as far as Cockermouth, and then the River Cocker up into the hills.

To the west lay the royal demesnes of Carlisle stretching down to Penrith, and the Barony of Liddel on the Scottish border north-east of Carlisle. The castles which acted as the seats for these strategically important lordships are not particularly well known, whereas those of the smaller lordships to the east are much more so. To a certain extent this is an accident of history since the eastern castles grew to become substantial and impressive fortresses which are prime tourist attractions today.

But how many people have even heard of the castles of Egremont or Cockermouth today? The royal castle of Carlisle is well known, as are the later and historically less important castles of Penrith, Brougham and Brough. In fact, it is not just that the seats of the Lordships of Allerdale and Copeland are not well known that is curious. The Lordships themselves are not particularly well furnished with castles at all. In fact, apart from the ruined castles of Egremont and Cockermouth, there are only two other castles which have been confirmed as dating to the 12th century, and one which dates to to the 14th. Other sites are classified only as possible sites of earthwork castles.

Northumberland is riddled with castles from the 11th and 12th centuries including the well-known Bamburgh, Newcastle, Norham, Durham, Alnwick, Wark-on-Tweed, Warkworth, Prudhoe. In addition there are less well-known sites like Wark-on-Tyne – although that was the seat of the Lordship of Tynedale, another lordship held by a Scottish family. Why were Allerdale and Copeland so devoid of them? To start with, I’ve put together descriptions and histories of the castles of this period within the two lordships. The two chief seats, Cockermouth and Egremont are written up in detail.

Lordship of Allerdale

Maryport, Castle Hill. This is an oval shaped mound surrounded by a ditch which was used to site a gun emplacement during the Second World War. The castle is sited in a horseshoe-shaped loop of the River Ellen close to the river mouth. There is no evidence of a bailey, and although the loop of the river would permit a bailey to have been sited there, it would have been vulnerable to flooding. The castle is close to the site of the point where the old Roman road crossed the river, and it was probably built to protect this strategically important route. Nothing is known of its history, but the design would suggest a late 11th/early 12th century site, and potentially therefore a castle of William fitzDuncan.

Cockermouth, Tute Hill. This site has been suggested as a predecessor to Cockermouth Castle and has been scheduled as a possible motte, but is one of a number of gravel mounds in the vicinity and may be either natural or a burial mound. It is about 3m high and 18m across, and is in a location close to the junction of the Rivers Cocker and Derwent, so it is sited in a suitable location for defence. Nothing specific suggests it is in fact the site of an earthwork castle.

Although this is traditionally the site of a castle built in the 12th century and the predecessor to Cockermouth, excavation has not found any evidence of a castle here. It is likely that the “castle” name relates to the Roman fort of Derventia which lay next to a road junction, although tradition associates the “Pap” part of the name with Gilbert Pippard, who married one of the daughters of William fitzDuncan and managed this part of the estate on her behalf, suggesting that it may have served some kind of function in this period. It is believed that stone from the fort was used to build Cockermouth Castle.

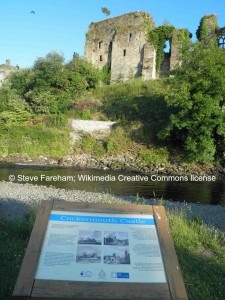

Cockermouth Castle. It is widely understood to be the case that the earliest incarnation of Cockermouth Castle was a motte and bailey erected by William de Fortibus in the mid 12th century in the angle of the ridge overlooking the confluence of the Rivers Derwent and Cocker. However, such are the natural strengths of the site that it appears unlikely that other sites nearby would have been chosen by prior Lords of Allerdale, particularly individuals like Wiliam fitzDuncan who were experienced warriors and actively involved in the civil war between supporters of Stephen and Matilda between 1135 and 1153.

In fact, Cockermouth passed in about 1147 to Alice, one of the heiress daughters of William fitzDuncan, and her husbands Gilbert Pippard and Robert de Courtnay, but she had no children to survive her. Upon Alice’s death, the Allerdale inheritance passed to the family of her sister Cecily (married to William d’Aumale), and to their heiress daughter Hawise in 1179. Hawise married William de Mandeville, Earl of Essex in 1180, and after his death in 1189 married William de Fortibus (II).

It was only in 1215 after the death of Hawise that her son William de Fortibus (III) came to hold what was referred to as the manor of Cockermouth. Fiercely protective of his rights, he rebelled against King John repeatedly and against the Regent Hubert de Burgh in 1220. In 1221, the castle of Cockermouth was taken by the Sheriff of Westmorland and sacked. This may suggest an attempt by de Fortibus to strengthen the fortifications at the site.

The castle motte is in fact a levelled area on the highest part of the ridge, and is only 2m higher than the courtyard “bailey” area, although it may originally have been separated from the bailey by a ditch, which would have increased the visible height difference. The bailey may also have had a defensive ditch, although this too has disappeared. The layout is similar to many earthwork castles in Scotland, particularly those on coastal and river promontories, providing defence in linear progression, which may suggest that fitzDuncan may have had a hand in the design after spending time in the northern realm. Having said that, the castle was rebuilt in stone in about 1225, so it is possible that the motte was levelled as part of this phase.

This second castle covered the area of the inner ward, was triangular in shape, and the foundations can be seen in the lower courses and foundations of some parts of the castle today. The entrance was probably at the southern end of the curtain wall by the Bell Tower, and the castle had a tower at the western end – overlooking the river junction – but nothing further survives today as the result of further development. If de Fortibus had strengthened Cockermouth between 1215 and 1221, this may reflect his earlier building, and be a third castle rather than a second one.

In 1241, the fourth William de Fortibus inherited Cockermouth upon the death of his father, and in 1260 when he died, he was succeeded by his widow Isabella. When the last of their children died in 1273, a commission was set up to determine who should be the next heir, and against all expectations that the de Lucy family would inherit, an alternative heir was found, an individual called John de Eston. John claimed to be descended from an otherwise unknown second daughter of William d’Aumale.

In an example of legal sharp practice, King Edward I managed to pronounce a claim of “unproven” to John de Eston’s claim, but at the same time to deny the claim of the de Lucy family. De Eston’s legal fees were paid by King Edward, and he went on to enjoy the income from a large part of the estates until he resigned his claim to King Edward in 1278 in return for a very small payment of £100. When Isabella died in 1293, on her deathbed she was visited by one of Edward’s private aides, and mysteriously sold the entire Isle of Wight to him in another potentially dubious transaction. Further legal claims by the de Lucys continued well into the reign of Edward II, until eventually Antony de Lucy was given the castle and Lordship of Cockermouth in 1323. The final case led to de Lucy being given another manor in 1336.

The de Lucy claim was very clear, namely that Amabil, the third daughter of William fitzDuncan, had married Reginald de Lucy. Their portion of the inheritance was Copeland, now firmly renamed as Egremont after the chief castle, and it passed to their son Richard in 1199 and his daughter Alice in 1213. Alice’s son Thomas adopted the surname de Lucy and inherited in 1287, his sons were Thomas (inherited 1305) and Antony, who inherited 1308. Antony was followed by his son Thomas in 1343, and Thomas’ son Antony in 1365 before another heiress, Antony’s sister Maud, inherited in 1368, and her two husbands, Gilbert d’Umfraville and Henry Percy carried out further repairs and alterations between 1368 and 1398.

Under Lady Maud Lucy, the Kitchen Tower was added at the north-eastern corner of the old castle, and an accommodation block was added along the eastern wall of the old castle, including a set of cellars and a chapel – which were built into parts of the old castle ditch, the rest of which was filled in. The inner gatehouse was built, and a new ditch was dug a little further out to enclose all the new building. In addition the eastern outer wall of the castle was demolished along with the towers, and a new wall erected slightly further out, again with a new ditch. At the north-eastern corner a new gatehouse was erected with a barbican, and the Flagstaff Tower was built at the south-eastern corner.

The de Lucy family further extended and developed the castle, heightening the curtain walls, rebuilding the western tower and adding the bell tower. An outer courtyard was then enclosed in stone. Slightly smaller than the current courtyard, a round tower at the southern corner, and it would seem logical that a second tower existed at the northern end of this wall as well – no suggestion of an outer gatehouse from this period has been detected to date, but it was probably a single gate tower.

For the remainder of its active life as a castle, Cockermouth remained a property of the Percy family. Henry Percy, Maud de Lucy’s husband, was the 1st Earl of Northumberland, the Earl who rebelled against Henry IV and was executed in 1408. His eldest son, known as Hotspur, had already died, so he was followed by his 15 year old grandson, also Henry. By this time a feud was developing between the Percys and the Neville Earls of Westmorland.

Unsurprisingly they appeared on opposite sides in the first battle of the Wars of the Roses in 1455 at St Albans, in which both Northumberland and Westmorland’s brother Salisbury were killed. Only six years later, the third Henry Percy was killed at Towton, fighting for the house of Lancaster. The seal of the third Earl named him as Earl of Northumberland and Lord of Cockermouth, reflecting how important the western lordship was to the Percy family.

After Towton, the estates of Northumberland were forfeited, and in 1466 Cockermouth was granted to Richard Neville, earl of Warwick (the famous “Kingmaker”). The attainting of the deceased Warwick after the Battle of Barnet in 1471 resulted in Cockermouth being returned to Henry Percy, along with his earldom of Northumberland. When the fourth earl died in 1489, he was followed by his son, the fifth Earl Henry, who was a prominent member of the courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII. He did not spend much time at Cockermouth, and the only record in his household books referring to his western estates refers to them as a source of income. When he died in 1527 it seems likely that the castle was falling into disrepair.

The 6th Earl of Northumberland, yet another Henry Percy, was engaged to Anne Boleyn when Henry VIII became infatuated with her. His father refused young Percy permission to marry her, but he appears to have remained in love with Anne, having a very difficult marriage with Mary Talbot which quickly resulted in estrangement. In 1536, when his health was failing, he announced that in the absence of children, and his intense dislike of his brothers, he was going to bequeath his estates to King Henry. Shortly after being one of the jurors who pronounced a death sentence on his beloved Anne, he collapsed and needed to be carried out of the court. The following year he died, and Cockermouth – much neglected as the 6th Earl always resided in Yorkshire when in the north – passed to the Crown.

The bequest to the Crown was on condition that the estates passed to Thomas, the nephew of the 6th Earl. He came of age in 1549, and came into much of his inheritance in 1552 – but not his titles, which did not get restored until 1557. From 1563 he had abandoned the north in favour of the royal court, but his loyalty to the Catholic faith meant that his loyalty was suspect.

By 1568 the castle was described as being in a state of decay, confirming that the western estates of the Earls of Northumberland had lost much of their value to the family. It was at Cockermouth that Mary Queen of Scots had landed in this year, and Northumberland felt he should have been given her keeping, but his protests only added to suspicion against him. In 1569, when the Earl had finally been pushed into rebellion, Cockermouth Castle did not even have an official keeper. In 1577, by which point Percy had been executed for treason, a survey of the castle reported that it was “in great decay, as well in the stone work as in the timber work thereof.” Tellingly the next sentence refers to the great worth of the lead covering the roofs. Thomas Percy was followed by his younger brother Henry, who ended his life in the Tower of London in 1585 – a verdict of suicide was produced, although this has to be doubtful as this was his third imprisonment for treason.

The 9th Earl was also a Catholic, and spent 16 years in the Tower of London because of suspicion that he was involved in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He had very little interest in Cockermouth and it was again largely left to decay. When his son Algernon succeeded him in 1632 as 10th Earl, he was even less interested. Educated in the south, he remained there as a member of the court of Charles I, although he quickly became associated with the opponents of the king. When civil war broke out, it was no surprise that Northumberland was a Parliamentarian, and installed a garrison of troops at Cockermouth.

In 1648 the castle was besieged, but to little effect. Although the accommodation was dilapidated, the defences were clearly still sound at this date. The following year, the inner ditch was filled in, and most of the roofs removed and presumably used for ammunition. The battlements were also removed, and by 1676 there were only four bedrooms, a kitchen and a dining room that could be used within the castle walls to stay in, although the bakehouse, stables and courthouse remained in service as well. By 1688 only the courthouse was of use.

The 10th Earl had been succeeded by his son Joscelin as 11th Earl in 1668, and Joscelin by his heiress daughter Elizabeth in 1670. Elizabeth married Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset, in 1682. In the 1740s it became clear to the Duke that the Percy estates would pass to his grandson-in-law Sir Hugh Smithson (an individual he personally detested and considered lowborn.) Whilst trying to prevent Smithson inheriting in communication with King George in 1748, Somerset died, and instead a deal was hatched between his son the 7th Duke and the King which would pass Cockermouth to the favoured grandson of the 6th Duke, Sir Charles Wyndham. Algernon Seymour, the 7th Duke, died in 1750, at which point Cockermouth became the property of Charles Wyndham along with the title Earl of Egremont (previously created for the 7th Duke). Charles lived until 1763, when he was succeeded by his 12 year old son George.

For over 50 years Cockermouth Castle stood empty and ruined, until George decided he would build some new and suitable accommodation in the outer bailey, and come to stay every July and August. A new range was built along the north wall, and stables along the south wall. Further buildings were added to fill the entirety of the north wall of the outer bailey along with offices along the east wall by 1850, by which time George had been followed by his illegitimate son George in 1836, created Baron Leconsfield in 1859.

George was followed by his son Henry in 1869, Henry by his son Charles in 1901, and Charles (having added further offices along the east wall in about 1904) by his younger brother Hugh in 1952. Hugh was also succeeded by his younger brother, Edward in 1963. Edward’s son John was created Baron Egremont in 1963, and succeeded father in 1967. In 1952 he died of cancer and was succeeded by his son Max who is the current owner of Cockermouth Castle. The family home, however, is at Petworth House in Sussex.

During the floods of early 2016, the River Derwent washed away a substantial amount of the riverbank, leaving the north wall of the old part of the castle dangerously close to the edge. Following discussion with structural engineers, emergency works carried out by Leconfield Estates involved a substantial deposit of rock being placed at the foot of the riverbank.

On 8th April Lord Egremont was interviewed and said “We were worried after the floods but think it is secure now. We had to move very quickly but got all these stones in place and diverted the river. We hope the stones in the river will secure the area, I think enough has been done. It does look precarious but I think it’s safe.”

Cockermouth Castle is clearly still a private residence, but is usually open in the summer for a few days during the Cockermouth Live! Festival. In 2016 the festival will be between 24th and 26th June.

Lordship of Copeland/Egremont

Beckermet, Caernarvon/Coneygarth Cop, Wodowbank Cop/Coneyside Cop. These sites south and west of Egremont are potentially a confusion relating to a single castle. Caernarvon Castle was a rectangular moated manor dating to the 12th century and demolished in about 1250. It was built by Sir Michael Fleming, who died in 1153.

Opposite this is a low rise called Coneygarth Cop which has been substantially reduced since it was described as an artificial mound 12 yards high in 1671, but may have been a motte.

A few hundred metres to the north-west is Wodowbank Cop, a low mound which has been damaged by the construction of a railway cutting.

A couple of miles further north-west is Coneyside Cop, which has also been suggested as the site of an earthwork castle, and had a plaque dedicated to the Fleming family dating to the 18th century. However, as the Flemings moved to Coniston after abandoning Caernarvon, this is likely a confusion. Ultimately, all these sites have been eroded away to nearly nothing, and only earthworks remain of the moated site.

As a matter of interest, the lordship was given the name Copeland because of the profusion of these “cops” or rises in the ground.

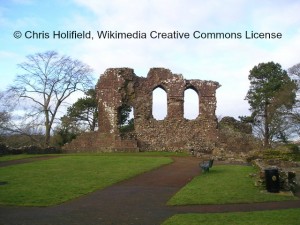

Egremont Castle As we have already noted, following the ejection of Dolfin of Cumberland by William II of England in 1092, the area was broken up into substantial baronies and most of it granted to Ranulf de Meschins. When Ranulf became Earl of Chester, the lands returned to the Crown, and about 1120 the barony of Copeland, incorporating the lands between the Rivers Derwent and Duddon was granted by Ranulf to his brother William. Later known as the Barony of Allerdale above Derwent, it was William’s principal territory in his own right, and here that he made his seat.

The site he chose was a prominent hill to the north of and overlooking a crossing point of the River Ehen. The highest point of the hill was at the north end, so here William strengthened the site to create a motte, separated from the bailey area to the south by a ditch. It is likely that Williams castle was built entirely of timber, with a small timber keep on the top of the motte to keep watch over the surrounding country and the river crossing.

William was married to Cecily de Rumely of Skipton in Craven (Yorkshire), the heiress daughter of Robert de Rumely. Occupying a rocky outcrop, Skipton had been built by Robert in 1090, and had been held by Cecily since that date. Their daughter Alice did not inherit Skipton until after her mother’s death in 1152, meaning that from 1135 Alice was Lady of Copeland. As we have seen, she was married to William fitzDuncan; their only son, William, drowned in about 1160 aged about 20, meaning that within a short time of her father’s death she was married to fitzDuncan.

The exact date of their marriage is important, but unknown. King Henry I of England had been patron to David of Scotland prior to his accession to the throne in 1124, and David was a supporter of Henry’s plan to appoint his daughter as Queen of England, invading on her behalf and applying much pressure to her rival King Stephen. Once David became king of Scots, Henry was less generous to his rival monarch. As Henry lived until 1135, the marriage of the heiress Alice – who would inherit not just Copeland but also Skipton – was in his gift, meaning that a pre-1135 date would have meant William fitzDuncan was a favoured knight of the English king. However, as a nephew of the King of Scots and possible Scottish Earl, William would be an unusual candidate for Henry’s favour.

What seems more likely is that the marriage took place after 1135. A substantial part of northern England was subject to David between 1135 and 1153, with control of everything north of the Ribble and Tees ceded to David. Practically speaking this means that the marriage of heiresses in this area was in the control of the King of Scots, who could therefore impose barons loyal to him in important lordships by means of marriage.

Another example of this is that of the Lordship of Tynedale – occupying the entire Tyne watershed from Hexham upstream. The heiress Hextilda was married to Richard Comyn, nephew of the Chancellor of Scotland. Unlike direct appointments to positions like the Bishopric of Durham (David attempted to get the Chancellor into this position), marriages were more subtle and more difficult to reverse. Placing his nephew in control of the Cumbrian coast while he controlled Carlisle provided David with a very strong strategic base in an area that had strong cultural ties to Scotland.

Following the death of William fitzDuncan in about 1147, his widow Alice retained control of Copeland, marrying Alexander fitzGerald in about 1155. FitzGerald was from Kingston Lisle in Berkshire, and was clearly someone who had little connection with Scotland. This reflects the changing circumstance of British politics with the accession of Henry II to the English throne, and also the death of King David.

Alice lived through almost the entire reign of Henry II. Her young son by William fitzDuncan, another William known as William of Egremont, died in about 1160; tradition (and a Wordsworth poem) tells the tale of his drowning in the river Wharfe, but it is also interesting to note that Fergus of Galloway led a substantial rebellion against King Malcolm IV of Scotland in the same year, and that the so-called “Rebellion of the Earls” against King Malcolm was also in that year. The nineteen-year old Malcolm had failed to win the approval of Henry II, and suffered poor health. In addition, the illegitimate brother of William of Egremont – Donald MacWilliam – was already rebelling in Moray. 1160 was a bad year for Malcolm with multiple risings against him, so it seems possible that William of Egremont, possibly in his early twenties by this time, might have been killed fighting in Scotland rather than drowning because his hound refused to jump across the river at the Strid.

Be that as it may, when Alice died in 1187, Egremont was inherited by her daughter Amabil, married to Reginald de Lucy. It is believed that in the time Alice was Lady of Copeland the old timber defences of the castle were replaced in stone. The oldest parts of the castle masonry are certainly dated to the late 12th or early 13th century, and can be seen in the main gatehouse and the wall to the north of it. Unfortunately we cannot say for certain when it was built. Amabil and Reginald had a son, Richard, who was Lord of Copeland from about 1200, but he died without a male heir in 1212, meaning that again a daughter was to inherit.

It seems most likely that during the time of Alice de Rumely or the de Lucy family, Egremont castle was entirely rebuilt in stone. The bailey area was enclosed with a curtain wall and a square gate tower three storeys tall was built at the south-eastern corner overlooking the river. The curtain wall crossed the ditch and ascended the note to enclose the summit, and it would be logical to think that the summit was enclosed by a shell-keep, a building known as the Juliet tower.

When Richard de Lucy died, his two daughters were placed in the custody of Thomas de Multon, who promptly married the girls to his two sons, and married Richard’s widow himself. For the privilege he had paid a thousand marks to the king. Although the younger brother Alan adopted the Lucy surname when he gained control of Cockermouth through marriage to Alice, his brother Lambert remained a de Multon, gaining the Barony of Egremont (not Copeland!) and occupancy of Egremont Castle. Lambert de Multon died in 1247, leaving his son Thomas to become Lord of Egremont.

It was most likely Thomas de Multon who decided to build a great hall between the motte and bailey of the castle, and it is the southernmost wall of this building that we see across the width of the castle today. At this time the ditch between the two areas had to be filled, and by this point an outer ditch had also been excavated along the west side of the castle. Part of this was later known to be a wet moat, but this may not have been an original defensive feature – more likely it was used as the castle fishpond. A final feature was added to the southern end of the castle, a round tower, but it is not known when this was constructed – not least because it is completely destroyed.

Thomas de Multon of Egremont was followed by his grandson Thomas in 1293. Thomas was a co-signatory into the legal case investigating the fitzDuncan inheritance put forward by his de Lucy cousins in 1306, and served in King Edward’s campaigns in Scotland. In 1316 Thomas was again involved in suing over for his inheritance, the result being that his son John gained a contract to marry the daughter of Piers Gaveston, the favourite of Edward II and who had been granted Skipton in 1308. In the end the agreement came to nothing.

In 1315, the year after the famous victory of Bannockburn, the Scots invaded northern England. In charge of the western invasion was James Douglas, and Egremont was one of the castles which was taken and sacked at the time, and when King Robert Bruce invaded a second time in 1322 he also despoiled Egremont. At about this time Thomas de Multon died, leaving Egremont Castle and its associated lands for his widow to enjoy. In 1335, John de Multon also died, leaving three daughters as heiresses, and Egremont passed to the eldest, Joanna, the widow of Robert fitzWalter (d1328). Joanna lived until 1363, two years after their son John, 3rd Lord fitzWalter, died, so she was succeeded at Egremont by her grandson, Walter as 4th Lord fitzWalter.

During the 14th century, possibly as the result of the double assault by the Scots, the curtain wall was raised in height, and the base strengthened. The fitzWalters held the castle of Egremont until late in the reign of Edward III, because Walter fitzWalter had to mortgage a third of his estate in order to raise a thousand pounds to buy his freedom from the French in Gascony.

It seems likely that the thousand pounds to ransom Walter fitzWalter had been provided by the Percy family, who were in possession of a third of the estate of Egremont in 1449. His grandfather was Henry, 2nd Lord Percy, and although Walter was followed by his son Walter (V) in 1386, he by his sons Humphrey (VI) in 1406 and Walter (VII) in 1415, and Walter (VII) by his infant daughter Elizabeth in 1430, the mortgage was probably never settled. As 8th Baroness fitzWalter, Elizabeth married John Radcliffe in 1444, and perhaps it was the transfer of the estate to another family that caused Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland to call the debt in.

However, it was not until the 1520s that the 6th Earl purchased another third of the fitzWalter estate and claimed possession of the castle. It is likely that the castle was damaged and abandoned during the “Rising of the North” in the 1570s, since a survey of the Percy estate in 1578 described the castle as “all most ruinated and decay’d save that part of the old stone work and walls thereof are yet standing, and one chamber therein now used for the courthouse in like ruin and decay.” It seems likely that although the building housing the Barony court remained in use in 1786 (and was therefore repaired) Egremont Castle was left to ruin from this date.

It is perhaps notable that the other substantial lordship held by the Scottish nobility in the northern borders of England was also only provided with a single castle, and again this is a site which has faded into obscurity. As substantial lordships on a border with a country England was often at war with, we would expect that a multitude of castles would exist from the 11th and 12th centuries, however there is not.

Perhaps this is a reflection on the fact that at the time, the Anglo-Scottish border was fluid and had shifted a hundred miles or so to the south. Perhaps it is a reflection on the attitude of the Scottish nobility towards castle building – there are certainly comparatively few castles dating from this period in Scotland itself. And finally, perhaps it is the case that the Cumbrian coast – considered important enough by King David to install his nephew in charge of it – lost its importance once the border shifted back in the 1150s and there was once more a strong King in England and a weakened one in Scotland. It is a question that perhaps deserves more attention than it has historically received. It was not until the 14th century and sustained warfare between the twoi realms that castles started to appear in more profusion across the north-west.

And so we have it. The large Cumbrian inheritance of William fitzDuncan, nephew of the King of Scots, and so important to the monarchs if the 11th and 12th centuries passed eventually to the Percy family. With their principal estates on the other side of the country, and the east being the principal point of invasion north and south of the border, the Percies valued their Cumbrian lands very little indeed as the area became increasingly a backwater particularly prone to cross-border raiding and cattle rustling.

One of the seats of barony is open to the public at all times, the other is partly a private residence and open only a couple of days a year. Yet these two castles may serve to remind us that for a few short decades, Scotland had its eyes very firmly on these lands as a prize worth having, and made marriages that were intended to create loyal Scottish barons in what is now one of the most popular English holiday destinations. I hope to visit these in the summer and to shre my own photographs afterwards.

Picture of Castle Hill, Maryport Picture of Cockermouth Castle Picture of the hall, Egremont Castle